OBITUARY

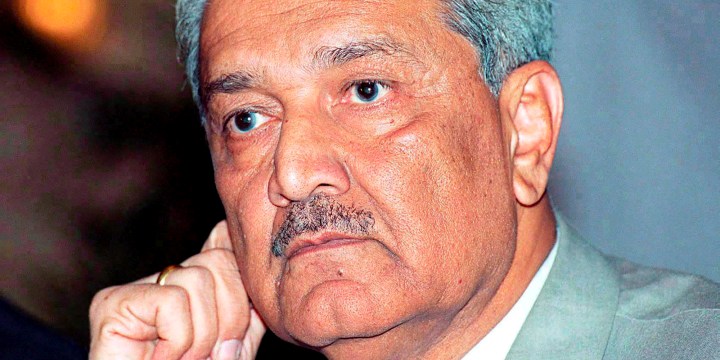

Nuclear serial proliferator Abdul Qadeer Khan — dead from Covid, but his weapons of mass destruction live on

By the time Pakistani nuclear engineer AQ Khan died, his energies had led to his nation’s own nuclear weapons force as well as efforts to pass nuclear technology to nations like Iraq, Libya and Iran — often for a fee. Khan’s life would make a film more terrifying than anything the James Bond franchise could deliver.

When the world’s first nuclear test exploded against the sky and across the New Mexico landscape on 16 July 1945, the lead scientist of the Manhattan Project, who had designed and built that device, watched with a mixture of awe and horror at what his team had achieved.

There was awe because the device was even more powerful than their calculations had predicted, and because the prodigious scientific and engineering effort had paid off. But there was horror, too, because of what this massive, unprecedented enterprise had unleashed upon the world. There was now no turning back; no shoving the genie back into the bottle.

Dr Robert Oppenheimer was that scientist, and as that first mushroom cloud rose into the sky, he told the others in their heavily shielded area, “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds,” quoting a line from the vast Hindu literary-religious work, The Bhagavad Gita.

Speaking of his memories later, Oppenheimer said, “We knew the world would not be the same. A few people laughed, a few people cried, most people were silent.”

However, once the two nuclear weapons were dropped on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki to force Japan’s surrender and end World War 2, few anywhere were silent any longer about such weapons. Oppenheimer, himself, was eventually barred from further government-sponsored physics work after he lost his security clearance, in part due to his statements about nuclear weapons.

In the years that followed that very first test at Alamogordo, Britain, France, the Soviet Union and China all followed with their own nuclear development programmes. Then it was India and Pakistan’s turn, and without public acknowledgement, the Israelis and the South Africans as well — and then, most recently, North Korea. Yet other nations such as South Korea, Germany, Taiwan, Brazil, Japan and Australia are routinely cited as being well positioned to convert their knowledge and experience with nuclear technology into serviceable nuclear weapons in very short time periods, if political decisions to do so are made to this end.

The growing number of nuclear-capable nations had fostered global pressure for an international nuclear non-proliferation treaty, now formally signed by 191 nations, although not by India, Israel, North Korea, Pakistan — and South Sudan (although the latter has other issues to worry about).

A generation later, another nuclear scientist, AQ Khan, had undertaken some rather different missions from Oppenheimer’s wartime exertions. Taken together, Khan’s legacy has become a particularly tangled one.

Khan died in Pakistan on 10 October at the age of 85, from complications related to Covid-19.

To some he is a hero, but to many others he was a real-life James Bond film-style villain and genius. Born in Bhopal, India, he moved to Pakistan with his family when British India was partitioned into two nations. He studied advanced metallurgical sciences in European universities and then worked for hi-tech European companies before returning to Pakistan. Regarded by many as the father of Pakistan’s own nuclear programme, his real speciality was with the complex nature of difficult-to-work-with centrifugal separations of fissile materials needed for nuclear reactors — and nuclear warheads.

In recounting events in 2003 in Libya that ultimately led to Khan’s downfall, the BBC described a man and his secretive network which had been active in making available some very detailed, technical information to nations such as Libya, Iraq or Iran. These were nations reportedly interested in developing their own nuclear weapons capabilities, despite having signed the nuclear non-proliferation treaty.

As the BBC described a secret mission to reclaim such valuable information from Libya, “… a group of CIA and MI6 officers were about to board an unmarked plane in Libya when they were handed a stack of half a dozen brown envelopes. The team were at the end of a clandestine mission involving tense negotiations with Libyan officials. When they opened the envelopes on board the plane, they found they had been given the final piece of evidence they needed: inside were designs for a nuclear weapon. Those designs — as well as many of the components for an off-the-shelf nuclear programme — had been supplied by AQ Khan.

“Khan was one of the most significant figures in global security in the last half-century; his story at the heart of the battle over the world’s most dangerous technology, fought between those who have it and those who want it. Former CIA director George Tenet described Khan as ‘at least as dangerous as Osama bin Laden’, quite a comparison when bin Laden had been behind the September 11 attacks.

“The fact AQ Khan could be described as one of the most dangerous men in the world by Western spies, but also lauded as a hero in his homeland, tells you much about not just the complexity of the man himself, but also how the world views nuclear weapons.”

Earlier in his life, Khan had been working in the Netherlands in the 1970s after Pakistan had been defeated by India in their 1971 war, and Pakistan was now increasingly focused on building a nuclear weapon to counter India’s own advances in that area. While in Europe, Khan had been employed by a company that built centrifuges that concentrated, or enriched, the isotope of uranium necessary for nuclear power — and if sufficiently further enriched — for a weapon. Before returning to Pakistan he copied the most advanced centrifuge designs, returned home and then built up a clandestine network, including a number of European businessmen, to supply crucial components for actually constructing centrifuges, and then, ultimately, nuclear devices.

While he was not the sole progenitor of Pakistan’s weapon, he had cannily nurtured the story that he was central to its construction, thereby turning him into a national hero. But it was his other effort that brought him into the international limelight — and ultimately his downfall. Flipping the purpose and direction of his network, he turned it into a channel for the export of information and technology, and doing deals with nations seen by the West as “rogue states”.

Describing his dealings, the BBC noted, “Iran’s centrifuge programme at Natanz, the source of intense global diplomacy in recent years, was built in significant part on designs and material first supplied by AQ Khan. At one meeting Khan’s representatives basically offered a menu with a price list attached from which the Iranians could order. Khan also made more than a dozen visits to North Korea where nuclear technology was believed to have been exchanged for expertise on missile technology.”

What has never been definitively clear was whether he was a kind of solo nuclear buccaneer or operating with the connivance or even under the secret orders of his nation’s government — or at least a part of it. In his dealings with North Korea, “all the signs are the [Pakistani] leadership were not just aware, but closely involved”, the BBC said.

Others have argued Khan was basically in it for the money, thus the buccaneer theory. And yet here, at least in his own mind, he also seems to have wanted to break a perceived Western monopoly on nuclear technology (forgetting about China and India, of course, which already had the bomb and are decidedly not of “the West”).

As Khan had said of his works, “I am not a madman or a nut. They dislike me and accuse me of all kinds of unsubstantiated and fabricated lies because I disturbed all their strategic plans.”

Meanwhile, before that fateful operation in Libya, Britain’s MI6 and the CIA had become sufficiently worried about Khan that they began tracking his travels, phone conversations and the members of his network, offering serious cash to get some of his crew to flip. One CIA official is quoted as having said, “We were inside his residence, inside his facilities, inside his rooms.” Following 9/11, there were growing fears terrorist groups — as opposed to nations — might gain access to such weapons.

By then, it had become increasingly clear that Libyan leader Moammar Gaddafi had decided to shutter his effort on nuclear weapons after observing the result of the 2003 invasion of Iraq. That, in turn, led to a deal whereby Libya would turn over those documents and materials, and that information then gave the US enough leverage with Pakistan to get the latter to rein in Khan.

As the BBC concluded, “Khan was placed under house arrest and even forced to make a televised confession. He would live out his remaining years in a strange nether-world, neither free nor really confined. Still lauded as a hero by the Pakistani public for bringing them the bomb, but stopped from travelling or talking to the outside world. And so the full story of what he did — and why — may never be known.”

In Khan’s statement, he had said, “It pains me to realise in retrospect that my entire lifetime achievement of providing foolproof national security to my nation could have been placed in serious jeopardy on account of my activities.”

Thereafter, Khan lived the rest of his life in a comfortable villa in a leafy part of Islamabad, but under the guard of heavily armed military personnel. Pakistani officials insisted they feared he might be kidnapped by foreign intelligence agents and interrogated. They allowed no access to him by nuclear inspectors from other nations or international bodies.

At least in Pakistan he was a hero. Following his death, AQ Khan received a state funeral and the Pakistani national flag was ordered lowered to half-mast to mark Khan’s passing. Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan praised Dr Khan for his “critical contribution” to making Pakistan a nuclear-weapons nation, adding, “this has provided us security against an aggressive, much larger nuclear neighbour. For the people of Pakistan, he was a national icon”.

Summing up AQ Khan’s place in history, Feroz Khan, himself a former official in Pakistan’s nuclear weapons programme, but who is now a professor at the US Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, California, said Khan had been able to set up a worldwide network to acquire the equipment needed and then managed the assembly of a bomb.

“Without Dr AQ Khan, Pakistan would not have had nuclear weapons,” Prof Khan said. “But his [AQ Khan’s] loose behaviour also endangered the Pakistan programme.”

Meanwhile, Mushahid Hussain, a Pakistan senator who was information minister in 1998 when Pakistan tested its nuclear weapon, said Pakistanis thought Dr Khan saved the country not only from India, but also from the US after the September 11 attacks, when Washington went to war with Afghanistan and then Iraq.

“AQ Khan is an authentic Pakistani hero. He defied the world, he defied the odds, he showed it can be done by a Muslim… by a Third Worlder.”

Michael Krepon, co-founder of the Stimson Center, a Washington DC think tank, said that Khan “took one for the team”, taking the blame for the sharing of technology abroad. Krepon judged that some of the proliferation was officially sanctioned, but other sales were Khan’s own entrepreneurship.

Through the system AQ Khan helped give birth to, Pakistan now apparently has some 165 nuclear warheads, compared with 156 warheads for India, according to an assessment published by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. But, crucially, says Krepon, “the system that AQ Khan built does not have a closedown switch.” In that sense, the potential of Robert Oppenheimer’s grim prophecy has come to be closer than ever.

“He was loved by our nation because of his critical contribution in making us a nuclear weapon state,” Imran Khan posted on Twitter. “For the people of Pakistan, he was a national icon.”

But AQ Khan, no relation to the prime minister, also confessed to being at the core of an operation that sold nuclear secrets to North Korea, Iran and Libya. Reuters analysts and United Nations officials have said his illicit network, which specialised in helping countries skirt international sanctions, created the greatest nuclear proliferation crisis of the atomic age. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

My guess is that Khan’s whole life view was affected by the partition of India and Pakistan in 1947 when he would have been 11?

Good article.

Except for this American propaganda line – “However, once the two nuclear weapons were dropped on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki to force Japan’s surrender and end World War 2 .. ”

That is not correct. The Japanese Emperor had offered MacArthur an armistice, but MacArthur had been humiliated by the ousting of forces from the pacific following the infamous Pearl Harbour bombing. And for that his demand was unconditional surrender. WWII could have ended much earlier in the Pacific had MacArthur agreed to the armistice, but he was one of the promoters of the murder of hundreds of thousands of Japanese civilians under those two atomic bombs because he wanted a complete and humiliating surrender.

The history books perpetuate the lie that the bombings were designed to end the war – the sole objective was to force an unconditional surrender. The Americans responsible should have faced a war crimes trial for that.

without him the world is probably a safer place!