Wide ranging factors are contributing to increases in Virginia energy bills — inflation, fluctuating fuel costs and renewable generation among them. But electricity demand for new data centers is driving expected costs, according to state research.

Running an electric grid is expensive work. Dominion Energy, Virginia's largest utility, is investing in renewable generation, as required by the Virginia Clean Economy Act. Renewables can have high upfront costs — particularly when building 176 wind turbines 27 miles out to sea, as the company is doing with its Coastal Virginia Offshore Wind project.

The price tag for that project recently rose 10% to $10.7 billion — though the facility won’t be accompanied by fuel costs.

The company also recently filed an application with state regulators for the natural gas-powered Chesterfield Energy Reliability Center, which could cost $1.47 billion, up from a reported $600 million for a similar plant in 2019.

“Turbine demand as well as inflationary pressures on material, equipment and labor costs post-COVID have all contributed to the current cost,” said Jeremy Slayton, a Dominion spokesperson, in an email.

Dominion said in its application that the project would save customers over $1 billion in costs that otherwise would be spent on transmission projects.

And the utility entered into a partnership with two other regional utilities to build out $4.6 billion of transmission infrastructure in Virginia, West Virginia and Maryland, though it’s not clear how costs will be divided among the utilities.

These power lines and substations will efficiently transport electricity over long distances, bringing it from where there’s excess generation to where there’s excess demand.

PJM Interconnection, which recently gave first approval to the batch of transmission projects, said the work is a needed stopgap to ensure grid reliability in the near future as demand projections spike and fossil-fueled generators are taken offline in some states to meet climate goals (including those set in the VCEA).

But perhaps the most important piece of the energy-costs puzzle is the facilities those transmission lines are being built to serve.

Data centers are driving the increase in energy demand

Northern Virginia has the highest concentration of data centers on the planet, and it’s upending many kinds of utility planning.

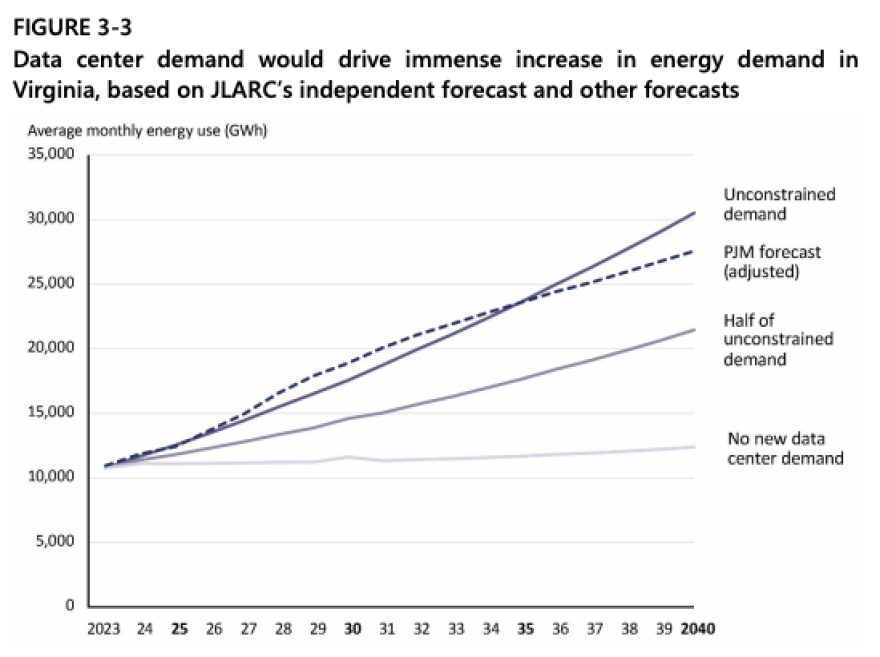

Not all data centers require huge amounts of energy, but the ones that do (called hyperscalers) are being built quickly in the Old Dominion: An analysis by JLARC, the General Assembly’s research arm, projects average monthly demand will double within a decade if data center growth is unconstrained.

Those facilities make up the vast majority of expected demand growth in Virginia — and that demand will have to be met with new infrastructure, like wind farms, gas plants and transmission lines. In some cases, that infrastructure will be paid for by the data center developers themselves, but changes are still coming to the grid.

Divvying up all those costs among customers is a complicated task for Dominion and regulators at the State Corporation Commission, but they follow a basic principle: Users pay for the cost of electricity they use.

Because electricity generation requires a lot of expensive stuff — power plants, transmission lines, substations, distribution networks, fuel — every watt-hour pays for a sliver of those costs. This principle basically holds for homeowners, small businesses and industrial facilities, which are divided into three rate classes.

According to the JLARC report, costs are currently allocated fairly among the three rate classes. That could change quickly, though, because the majority of new expected demand comes from data centers. JLARC said the costs could be borne by non-hyperscale customers in three ways:

- a portion of new infrastructure that would not otherwise be built will be paid for by customers other than those driving that new demand

- because meeting energy demands will be a challenge, costs will go up for all customers

- increased reliance on imports from other utilities means less control over those costs

What can be done about energy costs?

New infrastructure will have to be built to keep up with expected demand growth, and that infrastructure will be expensive.

Bill Shobe, a University of Virginia energy economist, agreed with JLARC’s findings, saying that with the commonwealth’s current rate scheme, some of the cost will be passed on to non-data center ratepayers.

“The thing is, that’s fixable,” Shobe said. “It’s fixable in the way we set rates.”

This is something the SCC is already looking at. It called a conference last year on grid impacts of new high-demand facilities, where commissioners heard from representatives of the data center industry, electric utilities and co-ops, environmental groups and ratepayer advocates.

It’s not clear how the commission will respond, but the comments could be taken into consideration in future ratemaking work. A bill to require action from the commission on rates failed at the General Assembly this year.

And there’s still a lot of debate about the most affordable approach to meet the demands of data centers. Solar and wind come without fuel costs, but need extensive battery buildout to be a viable, always-on source. Fossil fuel facilities, like CERC, are better suited to meet temporary spikes in demand, but require decades of additional fuel costs. Dominion is pursuing an “all-of-the-above” strategy it says keeps costs down while maintaining reliability.

According to Shobe, Virginia needs to have all the information to make the right decisions — but he’s not convinced regulators and legislators have it.

“Sometimes when we put polluting emissions up into the air, they're hurting people downwind, right?” Shobe said. “And yet, there's no price, there's no signal that, ‘Wow, I'm paying for this bad thing that's happening downstream.’”

He’s talking about incorporating the social cost of carbon, a measure that seeks to calculate the wide impacts of greenhouse gas emissions — rising temperatures, increased flooding, saltwater intrusion on agricultural land and sea level rise — facing Virginians today.

“These are real costs, in the sense that this is income we've lost, and we need to have some measure of these costs,” Shobe said.

The Virginia Clean Economy Act, a sweeping bill that includes Dominion phasing out carbon emissions by 2045, requires the company and regulators to consider these costs when examining the potential costs of building new power plants. They’re included in calculations as “shadow costs,” meaning the utility and its ratepayers aren’t responsible for paying them; the numbers just illustrate impacts of carbon pollution.

Shobe filed testimony with the SCC on Dominion’s most recent 15-year planning document, taking issue with the lack of a social cost of carbon calculation. According to Shobe, SCC staff agreed to allow Dominion not to include this calculation in previous long-term plans.

He testified that the projected average of 20 million tons of yearly carbon emissions included in the 15-year plan will incur a social cost of $10 billion.

There are also benefits to certain developments that might be unclear in rate proceedings — like CVOW, which is going to be the biggest wind farm off the East Coast when completed.

It’s expensive, Shobe said, but it’s also an investment in a growing industry.

“We don't want to just evaluate it on its cost,” Shobe said. “Does that make it cheaper to build the next one? Does it make us an industry leader, so we get more economic development out of it?”

The state has signalled its interest in more cutting-edge technologies — taking advantage of a large existing nuclear industry to pursue small modular reactors and grid-ready fusion power.

“The long and short of it is that with proper accounting and the right mechanism for rate setting … we can allocate these costs out properly,” Shobe said.