Ever since an engineer flipped a switch at Pearl Power Station in downtown Manhattan in 1882, electricity transmission around the world has traveled from point A to point B using wires. Whether through high-power transmission lines, low power distribution lines, or just the 120-volt socket in your kitchen, it’s wires all the way down.

While this may be fine for our homes, businesses, and iPhones, electric poles and wires don’t make sense for every situation, now or in the future. Maybe it’s simply too cost prohibitive to run cumbersome transmission lines or fiber optic cables to a remote island. Then there’s space applications. It’s not easy to run wires from solar-gathering satellites to terrestrial power stations. And with more industries going electric as part of the planet’s dire endeavor to eliminate carbon emissions, the ability to send power whenever and wherever it’s needed—wire or not—is more important than ever.

For more than a century, scientists and engineers have pondered a very different method for transmitting energy—without wires. It’s called power beaming, and for decades inventors, scientists, and engineers have been in a kind of technological dress rehearsal to make it happen. They’ve been tinkering with ways to use microwaves, radio waves, and even lasers to send energy from one place to another.

We could trace the idea for power beaming back to Nikola Tesla. One of history’s greatest inventors, Tesla always had some strange ideas. Some wound up changing the world (alternating current) while others were just, well, perplexing (a deep love of pigeons). However, Tesla could also be a technology soothsayer of sorts. In 1926 Tesla wrote in Collier’s magazine that “through television and telephony we shall see and hear one another as perfectly as if we were face to face” with devices that “fit in our vest pockets.” Vests didn’t really hang around, but the first smartphones arrived nearly 80 years later.

Then there’s arguably his most ambitious project—the World Wireless System. True to its name, the system could transmit electricity through the Earth’s ionosphere, essentially using the planet itself as a conductor—or at least that was Tesla’s hope. For financial, practical, and scientific reasons, Tesla’s World Wireless System faded into history. Yet, the idea of sending energy wirelessly lived on.

“Tesla was thinking about induction methods…he was thinking about using electric fields to then induce a current somewhere else,” says Stephen Sweeney, Ph.D., a professor of photonics and nanotechnology at the University of Glasgow. “That works well over short distances…but when you start to get far away, it doesn’t tend to be very good.”

The trick was figuring out how to direct the electromagnetic waves. Following the technological innovations of World War II, scientists had a couple of answers to this engineering conundrum: microwaves and lasers.

In 1964 American electrical engineer William C. Brown successfully piloted a small helicopter for 10 continuous hours via microwave power beaming. Fast forward to 1975 and Brown, along with NASA scientist Richard Dickson, successfully beamed 30 kilowatts of direct energy over one mile using microwaves beamed from an 85-foot, bowl-shaped antenna named Venus—but at only 50 percent efficiency. Both experiments were technical achievements to be sure, but not quite good enough—or scalable enough—to be immensely useful.

In the intervening decades, technological advancements began to push power beaming from a novel experiment into an energy necessity. These included the rise of computers, photovoltaics, lasers, and transistors. Society also began a push for electrification in the face of unrelenting climate change.

“When it was first proposed it was just technologically not possible…since then, the technology has evolved,” Sweeney says. “But in the last few years, what’s really made these sorts of things reemerge is that certain things have become cheaper to make.”

Rick Hodgson, the business development manager for the New Zealand-based power beaming company EMROD, sees the transition away from fossil fuels as another major reason why wireless energy transmission is finally being taken seriously. “Assets that were operated on fossil fuels are going fully electric,” Hodgson says. “A mining company in Australia announced a $4 billion deal with Liebher…to deliver over 450 fully electric vehicles.”

Now the challenge is that these electric vehicles need to recharge. But with power beaming, electric mining trucks, drones and satellites can potentially keep going while being continuously charged. The same is true for the increasing number of smart sensors that run our interconnected world.

All new technologies are competitive, but power beaming stands on its own. Part of the reason is that many wavelengths along the electromagnetic spectrum can be useful for power beaming. As with any energy source, the inevitable trade-offs depend on how this technology is used.

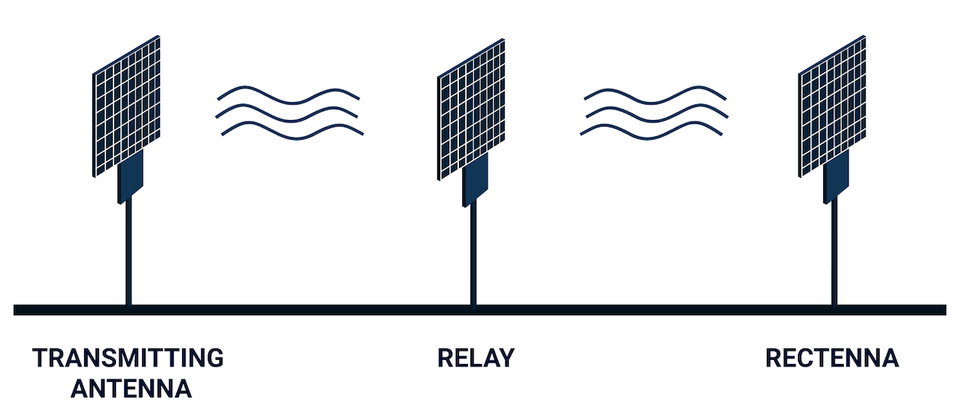

EMROD’s system, for example, starts with energy off the grid. The system converts that DC electricity into microwaves and transmits them in a collimated beam between a transmitting antenna to a receiving antenna. Finally, it converts the beam back into DC energy so it can be used. Most, if not all, power beaming set-ups work in a similar way, but the difference is the particular wavelength used between the two antennas.

Microwaves can pass through the atmosphere and don’t lose much power, says Sweeney, a photonics expert who has worked on many laser-based power beaming projects. “The big disadvantage is ultimately physics because…the ability to concentrate the beam is dependent on the wavelength.”

When beaming microwaves from relatively small distances, such as in an automated factory, or medium distances, such as to a remote island, the antennas can remain relatively small. But trying that same feat using solar-collecting satellites in space would require a receiving antenna that’s many square kilometers in size. Want to beam energy from a hypothetical Dyson sphere encapsulating the Sun? Forget about it.

Laser-based systems, on the other hand, have similar advantages and disadvantages, but in reverse. Lasers are more susceptible to atmospheric disturbances, but because their wavelength is in the micrometer range (not centimeters like microwaves), “you’ve got an ability to concentrate the beam much more and so you can make receivers small…the equivalent of a receiver for a laser-based space beaming is in the tens of meters,” Sweeney says.

Then, there’s the Goldilocks zone, where wavelengths are not too small but also not too large. This is where the U.S.-based Reach Power comes in, since its power beaming technology relies on radio waves in the millimeter range.

“I think that our use case is going to be under 25 kilometers,” Reach Power CEO Chris Davlantes says. While it won’t replace transmission lines across hundreds of kilometers, it could work for “a cityscape with robots, robo taxis, or drones in the sky, or distributed sensor platforms, or replacements for back-up generators.”

Power beaming is now a global effort, with investments in the U.S. funneling toward the military, and toward green energy in Europe. Asia has seen a big interest in telecom companies and Japan is leading the way in space-based power beaming. So with all these different applications, when will you see power beaming finally go mainstream?

It’s closer than you think.

Exciting technologies like fusion energy, flying cars, and other types of techno-fantasy always seem perpetually 30 years away. Yet, that’s not the case with power beaming.

“The first, near-term use cases…are really low power sensors,” Davlantes says. “Stuff that can be powered almost off of a wi-fi network.” Companies like Powercast and Wi Charge are already developing technologies for low-power sensors in the home and in retail locations. A few examples include smart lighting, motion sensors, and proximity sensors. Imagine walking down a supermarket aisle with dynamic displays that able to update remotely—all running on a power-beaming hub installed in the ceiling overhead.

But like most technologies that’ve been developed in modern history, the first adopters will most likely be outfits like the U.S. military, which can eat any energy inefficiencies or costs because the need for delivering power is so great. This is particularly valuable for the continuous operation of military drones or powering much-needed tech on the battlefield.

Efficiency is an obsession that fuels EMROD, which has worked with utility partners in New Zealand and around the globe to test its power-beaming technology. The company says its system of transmitters and receivers can achieve 95 percent efficiency—and they know how to reach 99 percent.

Ultimately, EMROD wants to build a global electric grid, including finding ways to power remote communities that aren’t well-connected for power. Called the Worldwide Energy Matrix, this space-based grid would essentially use a constellation of satellites to collect uninterrupted solar energy, transmit that energy between satellites, and send that power anywhere it’s needed around the globe.

The Japanese space agency, JAXA, is so motivated by this potential source of energy, that by the 2030s it hopes to have a space-based power station in orbit delivering one gigawatt of electricity—about as much as a commercial nuclear reactor does per year.

Even if such space applications might still live in that elusive realm of “just around the corner,” more terrestrial dreams for power-beaming are poised to be fulfilled. The technology is good enough, it’s cheap enough, and the initial skepticism that first pervaded the industry is fading into obscurity.

“At first…the questions I’d received in the early days were aligned with ‘this is impossible…there’s no way this is going to work,’” Davlantes says. “The biggest changes I’ve seen, even in the last five years…is that people now believe it’s real.”

Darren lives in Portland, has a cat, and writes/edits about sci-fi and how our world works. You can find his previous stuff at Gizmodo and Paste if you look hard enough.