Torkwase Dyson is not an abstract artist.

Despite her cult status among contemporary art devotees for her large, geometric sculptures, the Chicago–born, Hudson Valley–based artist insists that she is uninterested in abstraction for its own sake. Instead, she sees it as a coded language of Black liberation. “I’m interested in abstraction as a tool and a philosophy,” she explains. “I think of it as a field of study, just like history, political science, or literature … I’ve said it before—[I am] surviving abstraction with abstraction.”

Take, for example, the artist’s 2024 Whitney Biennial commission, Liquid Shadows, Solid Dreams (A Monastic Playground). From its perch above the Hudson River, the arcing sculpture—one of Dyson’s “hypershapes”—cut a hulking angular swath across the museum’s rooftop, drawing attention to a Manhattan area vulnerable to dangerous flooding. Dyson likens the work to an austere playground—visitors were encouraged to climb all over it.

When asked to elaborate on the role of minimalism in her practice, Dyson responds with a question: “How do you address surviving the brutal violence of erasure?” Liquid Shadows, Solid Dreams takes water as its focus—a broader conceptual throughline in the 51-year-old artist’s practice, which has confronted the interlaced socio-ecological perils of our time for over two decades. The issue of climate disaster and infrastructure has haunted her since Hurricane Katrina.

While Dyson was teaching at Spelman College in Atlanta, she welcomed some 30 displaced friends from the ravaged region until they were able to return home or settle elsewhere. “It was the definition of environmental racism,” she says of the natural disaster’s fallout. “I needed a multiscalar response. I started studying solar energy, zero-net architecture, the Army Corps of Engineers... anything that would get me closer to [understanding] why the levees failed.”

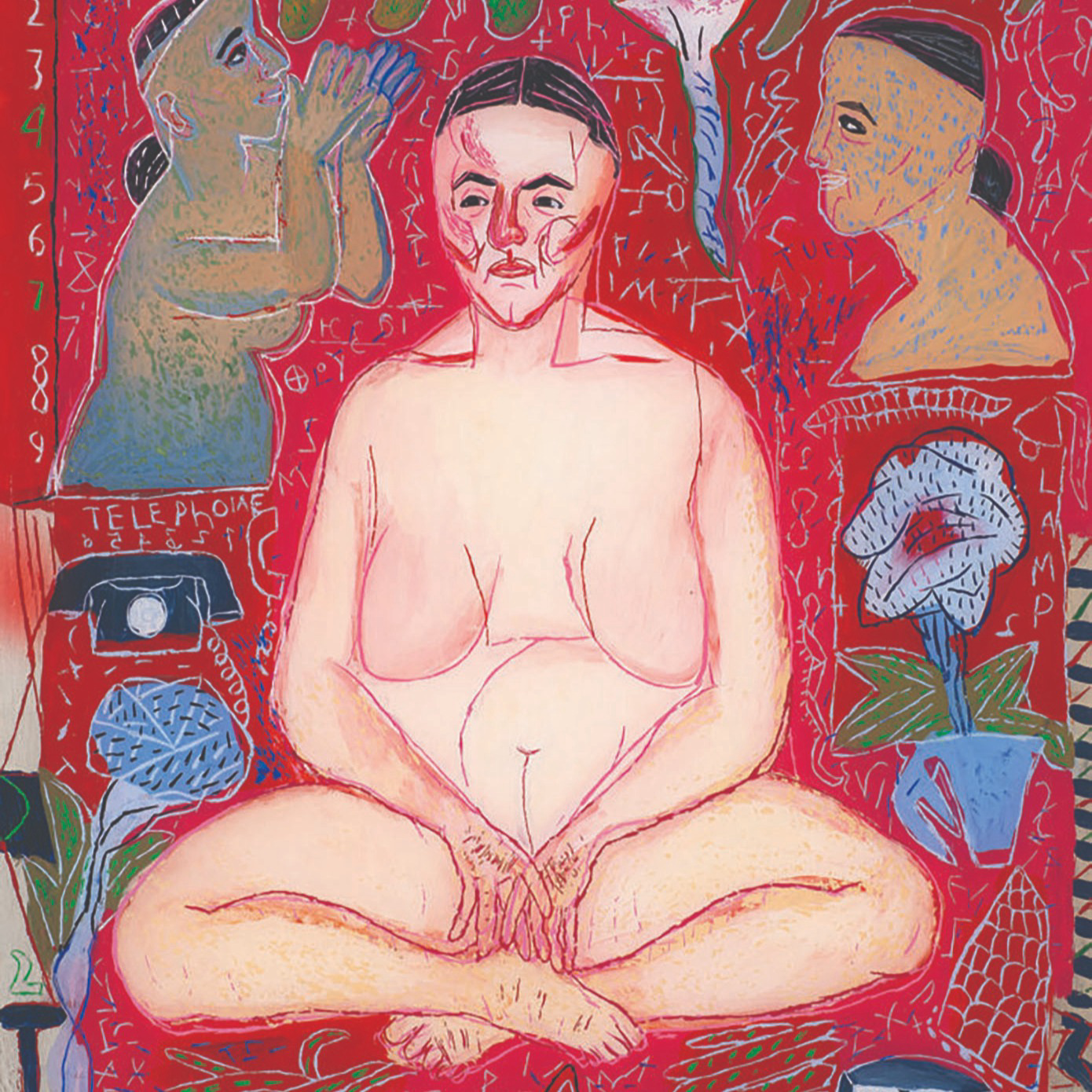

Shortly thereafter, Dyson began her “Black geography” series—stark, pared-down drawings responding to the ways that enslaved people “stowed [themselves] away in architectural space for freedom.” The forms would later become what she dubs “hypershapes,” symbolizing the paths certain historic enslaved persons braved to freedom. In Dyson’s sculptures, for example, the square evokes the crate of Henry “Box” Brown; the triangle, Harriet Jacobs’s garret crawl space; and the curve, the hull of Anthony Burns’s ship from Virginia to Boston in 1854.

Currently, Dyson is at work on two major projects that push her well past her comfort zone. In May, she will unveil her design for the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s “Superfine: Tailoring Black Style.” The Costume Institute’s annual spring exhibition—inspired this year by Monica L. Miller’s 2009 book Slaves to Fashion: Black Dandyism and the Styling of Black Diasporic Identity—explores the sartorial significance of the Black dandy, from the 18th century through the present. “The first challenge is the almost 10,000 square feet I need to fill,” admits Dyson. “Can this geometric space be a container for this kind of transhistorical Black life? It’s still a big question for me.”

That same week, the Public Art Fund will present an eight-channel soundscape by the artist in a sculptural pavilion in Brooklyn Bridge Park. “I wanted to give Torkwase an open invitation to respond to the space,” says Public Art Fund Senior Curator Melanie Kress, who witnessed the emotional impact of Dyson’s use of sound in the Old North St. Louis neighborhood in 2023, where a monumental curvilinear structure for the Counterpublic art festival looped the music of ragtime composer Scott Joplin. Powered by a solar generator, the black-painted wood sculpture, Bird and Lava (Scott Joplin), consisted of small stools for visitors to sit in its center, a bona fide open-air chapel.

“I saw the way she held space for people through art in the public realm,” recalls Kress. “That was the inspiration.”

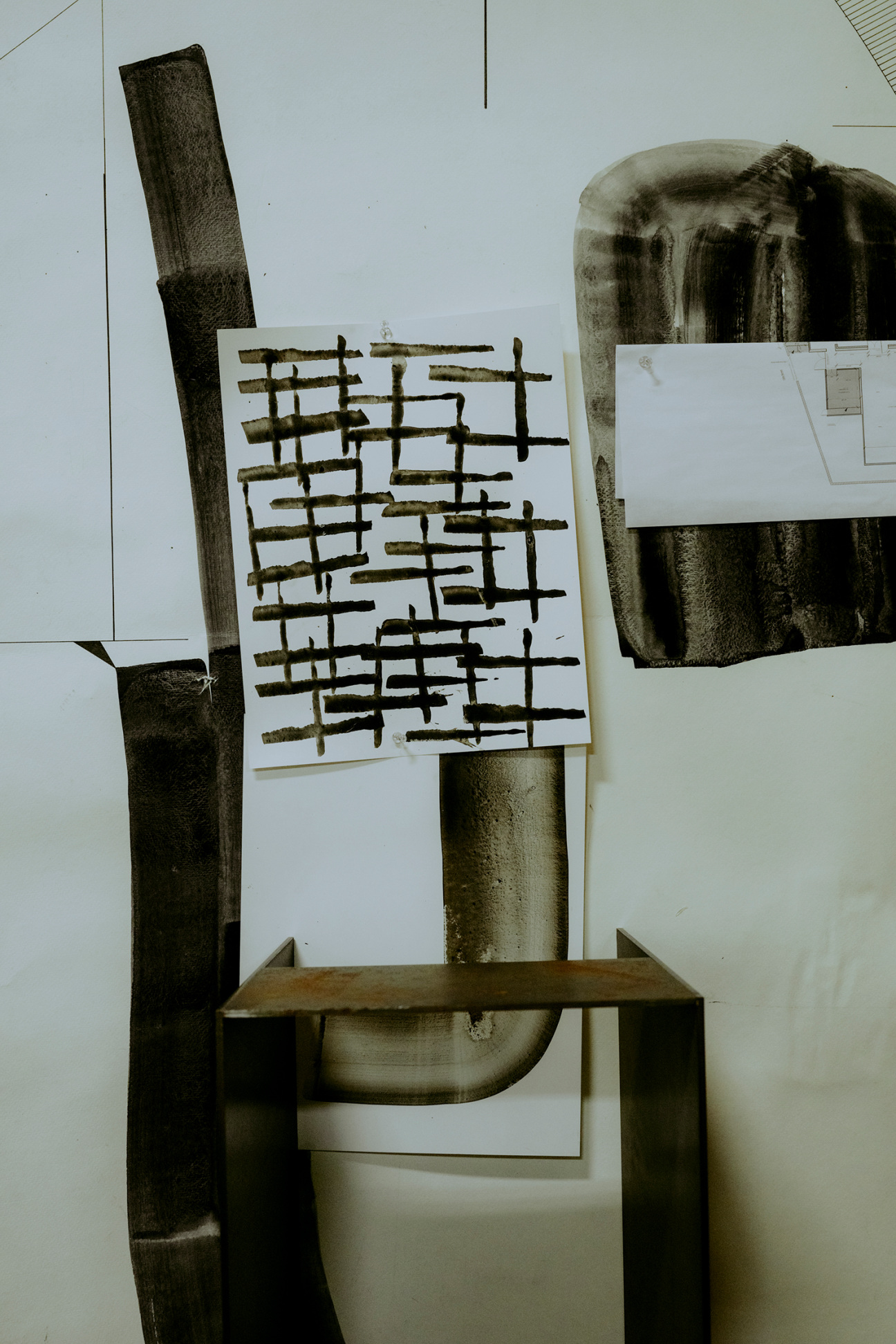

For the Public Art Fund commission, Dyson collected field recordings of family and friends talking and laughing to create a hyperreal soundscape that shifts as audiences move through the space. “I’m interested in a multisensory experience that emotionally connects us to the poetics of the space between our words—I’m thinking about this work as something between sculpture and architecture,” she says. “I wanted to think about sound through the lens of drawing—sound is a new medium for me, but if I think about the rhythm of the mark, I don’t get lost.”